UFC 3-210-10

25 October 2004

CHAPTER 4

STORMWATER MANAGEMENT USING THE HYDROLOGIC CYCLE APPROACH

4-1

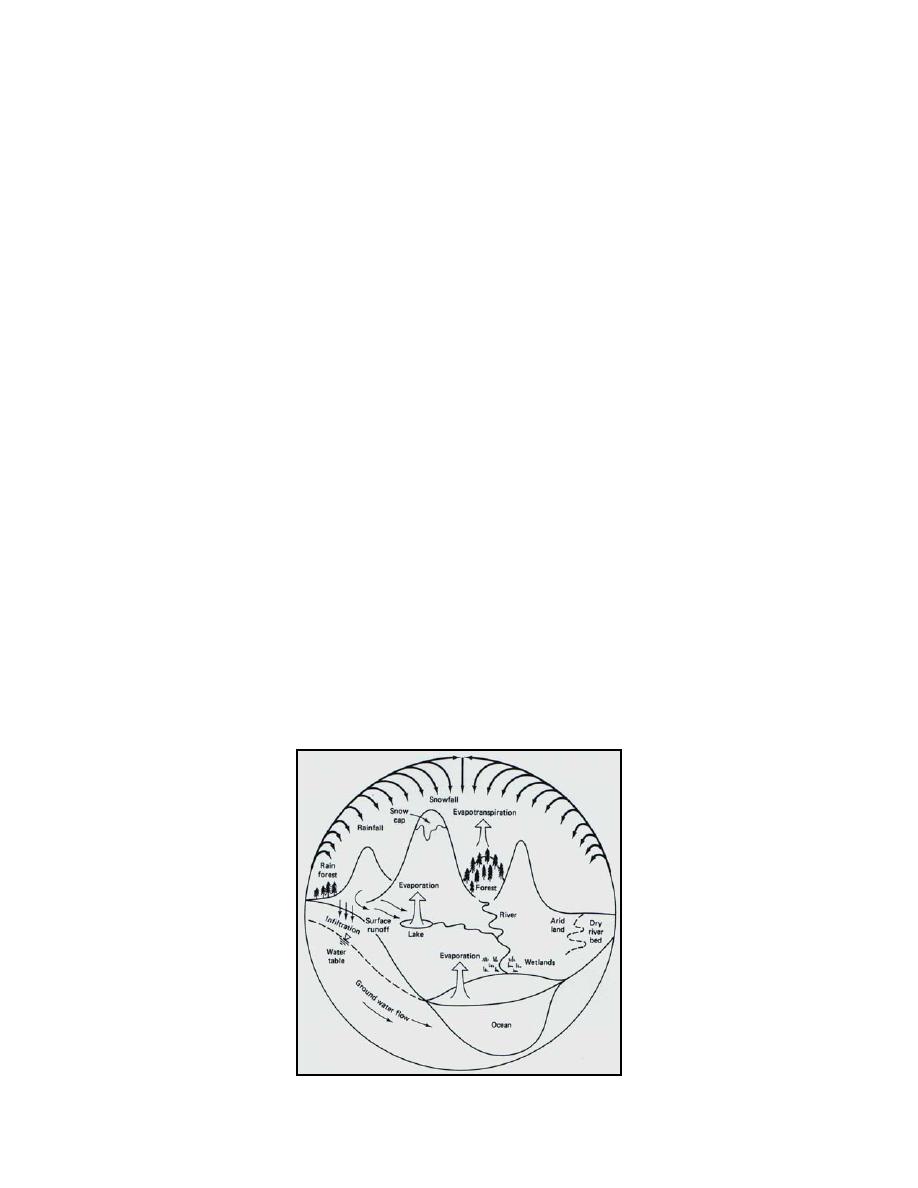

INTRODUCTION. Development affects the natural hydrologic cycle as

shown in Figures 4-1 and 4-2. The hydrologic cycle consists of the following processes:

convection, precipitation, runoff, storage, infiltration, evaporation, transpiration, and

subsurface flow.

A hydrologic budget describes the amounts of water flowing into and out of an

area along different paths over some discrete unit of time (daily, monthly, annually).

Grading, the construction of buildings, and the laying of pavement typically affect the

hydrologic budget by decreasing rates of infiltration, evaporation, transpiration and

subsurface flow, reducing the availability of natural storage, and increasing runoff. In a

natural condition such as a forest, it may take 25 to 50 mm (one to two inches) of rainfall

to generate runoff. In the developed condition, even very small amounts of rainfall can

generate runoff because of soil compaction and connected impervious areas. The

result is a general increase in the volume and velocity of runoff. This, in turn, increases

the amount of pollution that is carried into receiving waters and amplifies the generation

of sediment and suspended solids resulting from bank erosion.

4-2

DESIGN INPUTS. Both LID and conventional stormwater management

techniques attempt to control rates of runoff using accepted methods of hydrologic and

hydraulic analysis. The particular site characteristics that are considered will depend on

the nature of the project. Land use, soil type, slope, vegetative cover, size of drainage

area and available storage are typical site characteristics that affect the generation of

runoff. The roughness, slope and geometry of stream channels are key characteristics

that affect their ability to convey water.

Figure 4-1. Natural Hydrologic Cycle

Source: McCuen, 1998.

13

Previous Page

Previous Page